Basic Concepts

8.1 Introduction

Tk (short for “toolkit”) is the most widely used GUI toolkit for Tcl. There are several others, like Gnocl, based on Gtk, but in this tutorial we will only look at Tk.

Here is a simple program to illustrate the style of programming:

#

# For generality: load Tk

#

package require Tk

#

# Define the callback procedure used by the pushbutton

#

proc handleMsg {} {

tk_messageBox -title Message -message $::msg -type ok

set ::msg ""

}

#

# Create the widgets

#

label .label -text "Enter text:"

entry .entry -textvariable msg

button .button -text Run -command handleMsg

#

# Make the widgets visible

#

grid .label .entry -sticky news

grid .button -

#

# We want to be able to resize the entry ...

#

grid columnconfigure . 1 -weight 1

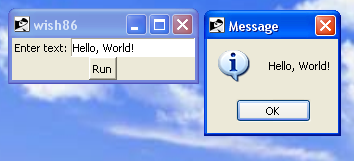

This program, when run in a Tk-enabled shell like wish, will show the window shown in Figure 1 (with details depending on the operating system and windowing environment).

|

| Figure 1: Example Tk GUI. |

In fact, this program will run in the command-line shell tclsh as well, thanks to the package require command.

You can fill in text in the text entry box at the right. If you press the pushbutton, a message appears and the entry box is cleared. You can resize it and only the entry box will become wider or narrower.

With just a few lines of code we have created a program that has a surprising amount of functionality. Even though it is small and does not do much of any use, the code does show many aspects you will find in actual GUI programs:

Creating the widgets (the elements of your GUI) is separated from arranging them in a window: the label command create a label widget (just some text that does not interact with the user), but you put it into its parent window using a geometry manager, in this case the grid geometry manager.

Widgets are represented by commands whose names start with a dot (.) Warning: after the dot you must have a lower-case letter. This has to do with the handling of display options.

Widgets often take options that connect variables to them, like the -textvariable option for the entry widget. Such variables should persist outside any procedure, so they are global by default, but you can also specify namespace variables. If you change the value of the variable, see the handleMsg procedure, then this is immediately shown in the connected widget.

Some types of widgets take a -command option that tells Tk to run a particular script when the user activates the widget. For the button widget that is: the user clicks in it with the mouse pointer. Since these scripts are not invoked in the context of any procedure, they run in the global namespace. It is good practice to use separate procedures (handleMsg for instance) instead of a complete script.

The geometry manager controls the placement of the widgets but also the resizing — if any. The grid geometry manager arranges widgets in rows and columns. More on geometry management can be found in Chapter 11.

Here are a few more aspects not shown in this simple example, but they will be discussed later on:

Widgets can be arranged in a hierarchy to make the geometrical management easier

You can create new independent windows (toplevel windows) that can be filled with their own widgets

Tk relies on options for the type of widget and on options that are set per widget. This gives you the freedom to change the appearance significantly without altering the code.

Besides the ‘classical’ widgets presented in the example, Tk as of version 8.5 also has so-called themed widgets. They are discussed in Chapter 14.

One very important aspect that is very much hidden in the wish shell is this: when the shell reaches the end of the script, it does not stop, but instead starts an event loop. Only when the event loop is running is the GUI alive: then it will display the windows, respond to actions from the user and so on.

As Tk is at least as dynamic as Tcl itself, you can easily experiment with widgets in an interactive shell. Just start wish and try commands like:

text .t pack .t

These two commands bring up what is essentially a complete text editor!